By the late 1930s the distinctive photographic tourism posters of the British Travel Association could be seen across the globe – in the USA, continental Europe, south America, and the Dominions of the British Empire. They advertised Britain as a land steeped in history and romance, perfect for the holidaymaker seeking old world charm or for the descendants of British settlers wanting to visit their ancestral home. The campaign was revived on an even greater scale after the Second World War, creating widespread press and overseas interest, yet relatively little has been written about the posters since. Consequently, it can be difficult to date individual posters, or even establish why they were printed in the first place and whether they were successful at the time.

To answer these questions, we need to go back to the 1920s, when Britain lagged far behind its continental rivals as an international holiday destination. Successive governments had failed to invest in tourism or provide strategic leadership, seeming instead to regard the whole business of national publicity as distasteful and un-British. What little attempt was made to promote the charms of the UK to overseas visitors was left to the railway and shipping companies and a few enterprising hoteliers. One of these, Sir Francis Towle (managing director of Gordon Hotels Ltd), founded the Come to Britain movement in 1926 to encourage a more joined up approach to international marketing. His efforts attracted the interest of the Department of Overseas Trade and, crucially, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Winston Churchill, who appreciated the potential for foreign exchange earnings to boost the British economy.

The result was the formation of the Travel Association of Great Britain and Ireland (TAGBI) in 1929, with a remit to “increase the number of visitors from overseas” and “stimulate demand for British goods and services”. Despite a small annual government grant, the Association was expected to be largely self-financing though a membership scheme, which initially included UK transport companies and organisations representing tourist attractions and related commercial interests. Under the direction of Douglas Hacking, a government minister from the Board of Overseas Trade, the Association quickly set about producing a range of printed publicity for worldwide distribution. Hacking was supported by an advisory committee drawn from some of the leading publicity men of the time, including FA Derry (Cunard), Cecil Dandridge (London & North Eastern Railway), E Huskisson (Thomas Cook & Sons) and GR Greenwood (Royal Mail Line). The Come to Britain slogan was formally adopted as the title for the campaign and was to remain in use until the creation of the British Tourist Authority in 1969.

At first, the Association concentrated on tourist publications, such as the popular Coming Events brochure launched in 1930 and printed in several languages. The literature was distributed through the government’s overseas outlets, international trade shows, and the Association’s own offices in New York (1930), Buenos Aires (1930), and Paris (1931). But the Association was always short of money and this restricted the amount that could be spent on printed publicity. In 1930, for example, the Association received just £5000 a year from the government, with subscriptions from members adding another £18,000 – a paltry sum compared with the £300,000 invested by the French government on marketing. “The more one learns about the work of the Association in its effort to ‘sell’ England”, wrote the journalist Charles Graves in The Sphere (1933), “the more one realises the childish lack of support it secures. No wonder the English spas do not get the patronage of foreign visitors”.

As far as poster publicity was concerned, this meant that the Association initially used the existing designs of its member organisations (especially the railway and shipping companies), rather than commissioning and printing its own. This can be seen in the photograph of the Travel Association’s Paris office (below), which includes contemporary posters published by the London & North Eastern Railway and the London, Midland and Scottish Railway alongside leaflets printed by the TAGBI.

Funding remained a problem throughout the 1930s, but some relief came in 1931 when a change in the law enabled local authorities in England and Wales to contribute to the costs of overseas advertising for the first time. This voluntary scheme allowed councils to levy ½ penny on the rates to pay for promotion via the Travel Association. This in turn transformed the Association’s ability to market specific locations, although many councils were slow to take up the opportunity. By 1933, for example, the major tourist centres of York, Winchester, Salisbury, Weymouth, Worthing, Oxford and Cambridge were yet to join the scheme.

Those councils that did take part, however, were keen to promote the uniqueness of their locality, with poster advertising offering an obvious solution. Many also wanted to use the same channels to promote their industry, as there was little support from government to coordinate international trade initiatives. In response, the Association changed its name to The Travel and Industrial Development Association of Great Britain and Ireland (T&IDA) in 1932 in recognition of this wider inward investment role, although it’s doubtful whether the Association’s core activities changed much as a result.

One of the first posters produced during this period was jointly commissioned by the Lancashire Industrial Development Group and the Travel Association to encourage new manufacturing and tourism to the region. Designed by the progressive Ralph Mott Studio, the graphic design blends industrial views of Liverpool and Manchester with more obviously tourist-focussed images of Blackpool, Preston and the surrounding countryside. This combination of business and recreational opportunities shows a modern understanding of place selling, but it was to prove far from typical of the Travel Association’s poster output which favoured photographic representations of individual UK destinations.

A possible reason for this is that the Association was building up an extensive photographic library to support its wider promotional activities and it may have simply proved cheaper to repurpose these images than commission poster artists. By the mid-thirties the range of TA publications had grown significantly to include hotel guides, regional brochures, pocket calendars, press-packs, and monthly newsletters, printed in several languages. These were supplemented by newspaper advertising, exhibitions, lantern slides, radio broadcasts and films. Frustratingly, contemporary sources are silent about the guiding aesthetic behind the Association’s advertising, which in retrospect seems to have more in common with the black and white photography of the contemporary Shell Guides to Britain series than the highly coloured graphic treatment of traditional travel publicity.

Although difficult to date with certainty, it seems that the Travel Association’s poster campaign didn’t get into full swing until the mid-30s. Towns that relied on tourism for a significant slice of their income were first in the queue, with printing costs split between the local authority and the Association. Margate, for example, supported the production of 3,000 posters for distribution by the Association in 1936. In December 1938, the executive committee of the T&IDA reported that twenty different photographic posters had now been printed, with several more in the course of preparation. One of these was for Dover, where the local authority agreed to spend £50 on printing 3,000 posters after seeing examples for rival south coast resorts. Ramsgate, too, was said to have committed funds for the 1939 holiday season.

No complete list of Travel Association posters from this period appears to have survived. Known examples exist for Bath, Blackpool, Bournemouth, Brighton, Chester, Chesterfield, Dover, Eastbourne, Folkestone, Leicester, Lincoln, Llanberis, London, Margate, Morecambe Bay and the Lake District, Norwich, Portsmouth, Ramsgate, Stratford-upon-Avon, Sunderland, Tewkesbury, and Winchester. It’s an odd list, with obvious ‘gaps’ for most of Wales and major English seaside towns like Skegness (poster publicity for Scotland and Northern Ireland, it should be added, was managed separately by the Scottish Tourist Board and the Ulster Tourist Development Association working with the Travel Association). Doubtless more will turn up, but it’s clear that some English and Welsh local authorities remained sceptical of the benefits.

The surviving posters, however, form a remarkably unified group in terms of design and production. Intended to be displayed in travel centres and information bureaux, rather than on the hoardings, they were printed in a standard Double Crown (30 x 20 inches) format to an incredibly high standard. The photographs, often by significant documentary photographers including John Dixon-Scott and Herbert Leo Felton, were reproduced by a technique known as photogravure which gave an astonishing depth and tonal subtlety to the final image. This process required the skills of specialist printers, such as Rembrandt Photogravure which printed most of the Association’s posters in the late ‘30s. Typographically, too, the posters were connected by a shared, modernist, typeface which declared whether the location was in England or Wales. Interestingly, the actual placename was printed in a small size within the image, while the Association’s slogan Come to Britain was omitted altogether.

Quite how these black & white photographic posters fared next to the Art Deco graphics of Italy and France is a moot point. But according to an article in Art & Industry (1936) the selection of images was based on extensive market research into the travel habits of foreign visitors to the UK. Tourists from the USA and the continent were said to be especially well-informed about British history and eager to see different parts of the country during their stay. For this reason, the Travel Association also promoted tours of the British Isles by rail, car, coach and plane.

Assessing the success of the pre-war advertising campaign is clouded by factors outside the Association’s control. Overseas tourism to Britain certainly increased in the 1930s, up from an estimated 475,000 visitors in 1932 to over 720,000 by 1938 (the last full year of peace). This was in part due to the recovery of the American economy after the Depression and the increasingly unsettled nature of continental politics that made Britain a more attractive place to visit. But the Association had also played a significant role in publicising the UK and in persuading the government that tourism made an important contribution to the British economy – a fact reflected in the increased subsidy paid to the Association on the eve of the Second World War.

Not surprisingly, the work of the Association was considerably wound down during the war, with just a skeleton staff maintained at the organisation’s HQ in Pall Mall. Even so, the importance of tourism for the post war economy was recognised in a government report authored by the Travel Association, Britain – Destination of Tourists (1944), which recommended the creation of an official government run tourist organisation once peace returned. This was effectively enacted by the Labour administration in 1947 with the creation of the British Tourist and Holidays Board (BTHB). The renamed Travel Association of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland became the tourism division of the new board, having already dropped the pre-war commitment to ‘industrial development’.

Despite post-war paper shortages and other difficulties, the Travel Association distributed an estimated 3.5 million publications and 500,000 posters in 1946/7. Government support had risen to £100,000 pa, with a further £75,000 raised from membership. This figure continued to rise during the 1940s, reaching a combined total of £436,000 by 1948/9.

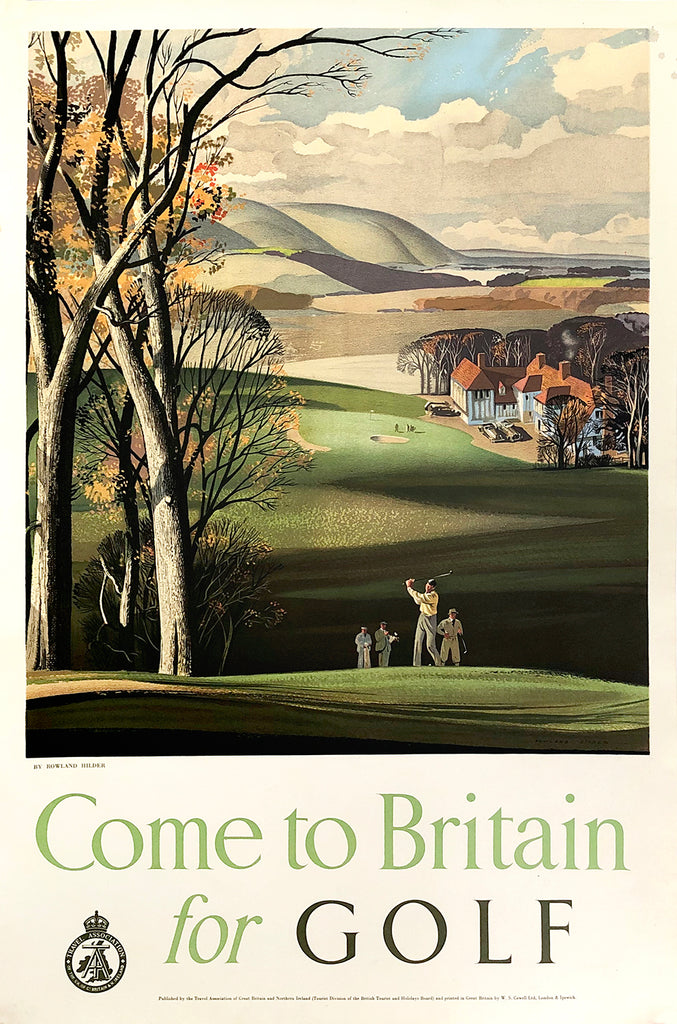

In May 1946, the Travel Association announced a new series of six full-colour posters under the Come to Britain slogan. These posters differed from pre-war TA campaigns in using generic, non-specific, locations painted by well-known artists:

- Come to Britain for Yachting, Arthur Burgess

- Come to Britain for Hiking, Brian Cook

- Come to Britain for Motoring, Norman Hepple

- Come to Britain for Fishing, Norman Wilkinson

- Come to Britain for Horse Racing, Lionel Edwards

- Come to Britain for Golf, Rowland Hilder

Printed in 1947, 60,000 were distributed to the USA alone, with further copies going to Argentina, Hungary, Brazil, Scandinavia, Netherlands, Belgium, France, Switzerland, Portugal, and Commonwealth countries. The aim, according to a TA press release, was to circulate the posters in advance of the London Olympic Games (1948) as part of a wider government publicity drive. The series was very favourably reviewed in the press, although some eyebrows were raised at the wisdom of advertising Britain as a place for motoring during a period of petrol rationing!

In tandem with the Come to Britain poster campaign, the Travel Association relaunched its pre-war series of photogravure destination posters with at least 50 new posters appearing between 1947 and 1949. The new series was printed in both Double Crown and Double Royal (40 x 25 inches) format on poorer quality paper stock than before. Image reproduction was also generally poorer than in the 1930s, although there is considerable variance between different designs. The pre-war lettering was replaced with a more modern style and the Association’s new logo. Out, too, went the ‘England’ and ‘Wales’ titles to be replaced with ‘Britain’ in recognition that TA posters now represented Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Local authority members were still expected to bear some of the production costs, with print-runs in the region of 10,000 copies. Councils sometimes supplied the photography as well, usually in association with the local newspaper. FJ Zenas Carter, the photographer of the Royal Leamington Spa Courier, for example took the image below, which was described by the local council as “undoubtedly the best picture ever to be issued in praise of this elegant thoroughfare in the Royal Spa”.

Town councils generally seemed to be very pleased with the Travel Association posters, which were often reviewed in local papers and exhibited at art galleries. The Dover Express (18/02/1949) thought their council’s poster was bound to result in increased tourism thanks to the “magnificent view of the Castle, with the harbour in the foreground” (below).

But not everyone was so impressed. The posters’ emphasis on the historic aspects of Britain was seen by some to be at odds with the desired image of the UK as a modern industrial nation. At a meeting of the Nottingham Chamber of Commerce (1948), the local MP, Geoffrey Frietas, expressed disappointment at the council’s Travel Association poster, arguing that “England is not a national park, not a museum of castles and cathedrals, but a living, moving, highly industrial twentieth century country.” His views were shared by the Birmingham Daily Gazette which thought that the city’s poster featuring the Town Hall “does not represent the true Birmingham – the industrial Metropolis of the Midlands” (1949).

Such complaints, which tended to come from manufacturing towns, fell on deaf ears. As the official history of the British Travel Association (1970) put it, “[by] the later ‘sixties … it became generally realised that overseas visitors were attracted by the unique characteristics of a country, rather than by bigger and better power stations ……. the Association was in the right to concentrate in its promotion upon the very things which made Britain different.”

As the 1940s drew to a close, the black and white Travel Association posters began to look a little old fashioned. A new series of full colour posters appeared in 1948, depicting an idealised Britain in the four seasons. Again, they were painted by leading artists and distributed worldwide:

- Britain in Winter, Terence Cuneo

- Britain in Spring, Donald Towner

- Britain in Summer, Ernest Haslehurst

- Britain in Autumn, Norman Wilkinson

They were followed in 1949/50 by a similar series featuring the Inns, Abbeys, Cathedrals and Castles of Britain, with designs by Leonard Squirrel, Donald Towner, RG Brundit and Norman Wilkinson. The gradual easing of austerity, and developments in cheaper methods of colour photographic reproduction, also enabled the Travel Association to experiment with colour photographic posters, the first of which began to appear in 1950. In the same year, the British Tourist and Holidays Board was reconstituted as the British Travel and Holidays Association, which is where our story ends. It was not, of course, the end of posters advertising Britain overseas, which continued through to the formation of the British Tourist Authority in 1969 and beyond.

In compiling this blog post, I have made extensive use of the British Newspaper Archive (https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/), The British Travel Association 1929-1969, by Ray Hewett et al (1970), and various issues of Commercial Art and Art & Industry. As always, I’d be delighted to hear from readers with further information about this poster series, including omissions/corrections etc.

We always stock a selection of original, vintage, Travel Association posters for sale, which can be viewed here.

Known post-war examples of photogravure Travel Association posters exist for: Aberystwyth, Balmoral, Bath, Beachy Head, Belfast, Ben Nevis, Birmingham, Brig o’Doon, Brighton, Buxton, Carlisle, Cheltenham Spa, Chesterfield, Deal, Dover, Droitwich Spa, Durham, Edinburgh, Folkestone, Fountains Abbey, Giant’s Causeway, Harlech, Hastings, Hereford, Herne Bay, Highlands, Hull, Ilfracombe, Leamington Spa, Leicester, Liverpool (Speke Hall), Llandrindod Wells, Loch Nevis, London, Mourne Mountains, Newport, Oxford, Raglan Castle, Ripon, Shrewsbury, Southampton, Southend, St Albans, Stamford, Stratford upon Avon, Swansea, Teignmouth, Torquay, Tunbridge Wells, Warwick, Wells, Whipsnade Zoo, Whitby, Winchester, Wisbech and York.

Comments on post (2)

Martyn Atkins says:

I would love to find an original of the Stamford poster: at present only available online in poor-quality reproductions…

Tim Bloomfield says:

Excellent

Leave a comment